Direct response has always been popular among marketers. The allure of it is simple and straightforward. An organization sends out, let's say, 1,000 direct mail letters with an offer and 10 percent of those who receive the offer respond. That is your response rate. That is your return on investment.

I intentionally used the direct mail letter as an example because direct response used to be associated with mail. The truth is, of course, that it has included call to action ads and television commercials, coupons, telemarketing, broadcast faxing, email marketing, and a host of online tactics that range from pop-up ads to paid placement on search engines.

The only reason direct mail remains associated with this niche marketing tactic is because that is where it started, with Aaron Montgomery Ward producing the first mail-order catalog in 1872. This won't always be the case. Direct marketers are more likely to call the field data-driven marketing.

It's still very popular too. In 2012, the Direct Marketing Association estimated $156 billion was spent on direct marketing under its new moniker data-driven marketing. I've read elsewhere that data-driven marketing accounts for as much as 8 percent of the GDP in the United States. That's a ton.

So what's wrong with that? Nothing really, except for the growing number of marketers that are attempting to apply direct response rates to every bit of communication. It doesn't work that way.

People who only measure the immediate suck the results out of their long term.

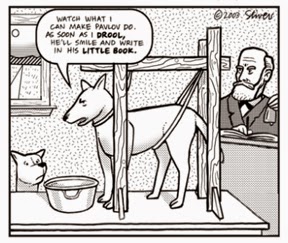

If we were talking about fitness, I might liken direct response marketers to people who step on the scale every morning to check their weight. If the scale reads minus one pound, they feel successful. If the scale reads plus one pound, they feel defeated.

Ask someone trying to lose weight and they might even confess that anytime they gain a pound, they are compelled to inventory everything they did and ate the day before as if they could pinpoint its origin. Was it because they cut their cardio short for five minutes? Was it the turkey on their salad at lunch? Was it the half-glass of 2 percent milk they drank at dinner?

No wonder people who diet are so easily defeated. They are constantly measuring the wrong thing, thanks in part to this odd obsession with weight in most anti-obesity campaigns. But it's a mistake because body composition (not weight) is the cornerstone of a successful fitness program. And to successfully change your body composition, you need process goals as well as performance goals.

Marketing, advertising, and public relations work much in the same way. The total composition of your strategic communication plan has a greater long-term impact than any single piece or part. So while you can measure the direct response of almost anything, one pound either way means nothing.

Where is direct response measurement starting to infringe on effective communication?

Public Relations. More and more firms are allowing themselves to measure the number of pickups, total impressions, and advertising rate value delivered by each news release. But doing so creates an erroneous impression that some releases or pitches are good and others bad. The truth is, however, that relationships with the media cannot be measured by whether or not a reporter picks up a story. Provided the pitches and releases are grounded in having news value, even if you think they are ignored, they could eventually prompt a reporter to call out of the blue looking for an expert source.

Advertising. Every now and again, I share the story of an attorney who was convinced that the bulk of his marketing budget should be invested in the phone book yellow pages. When asked why, he was perplexed that it wasn't obvious. They spend more money where they get the most response. But that wasn't true. The attorney only received his greatest response from the phone book because that is where he invested the most marketing dollars. A better composition, not more money, eventually delivered a better response.

Social Media. Social media specialists and search engine optimization experts alike are often quick to judge the quality of content — whether it's a video, blog post, or tweet — by any number of direct response measures such as likes, shares, or incoming keyword traffic. While these measures are always good to look at, they also skew the story toward the first impression and not the final outcome or total user experience. Marketers need to remember that reputation is built by the total body of work.

Journalism. More than ever before in the history of media, journalism has become a populist medium. Reporters are less likely to cover stories that the public may find interesting and much more likely to cover stories that the public already finds interesting, which is grounded in direct response. The recent death of one particular actor and comedian may even be the tipping point. I don't recall someone's death ever being exploited as much as this one. But the media won't let up because the response rate is encouraging the exploitation.

There are dozens of examples. It's why Mat Honan can produce a wacky reality simply by liking everything on Facebook. It's why the greedy coin algorithm will usually fail. It's why author-photographer Geoff Livingston couldn't reconcile how the algorithms see art. And it's precisely why most people quit exercising when they don't see their weight change (as muscle replaces fat).

So while direct response will always be worthwhile (especially when it is enhanced by creativity, timing, and proper targeting), it doesn't mean direct response measurements and other algorithms can be applied to everything. If they were then Vincent van Gogh would have been lost to history and the person you're mostly likely to marry is simply quantified by a successive run of good dates.

So don't be fooled. Good marketing only looks simple because it is complicated. Sure, direct response has its place (much like weight) but only if your process goals and performance goals are designed to deliver the right strategic communication composition. And that's the truth, "like" it or not.

I intentionally used the direct mail letter as an example because direct response used to be associated with mail. The truth is, of course, that it has included call to action ads and television commercials, coupons, telemarketing, broadcast faxing, email marketing, and a host of online tactics that range from pop-up ads to paid placement on search engines.

The only reason direct mail remains associated with this niche marketing tactic is because that is where it started, with Aaron Montgomery Ward producing the first mail-order catalog in 1872. This won't always be the case. Direct marketers are more likely to call the field data-driven marketing.

It's still very popular too. In 2012, the Direct Marketing Association estimated $156 billion was spent on direct marketing under its new moniker data-driven marketing. I've read elsewhere that data-driven marketing accounts for as much as 8 percent of the GDP in the United States. That's a ton.

So what's wrong with that? Nothing really, except for the growing number of marketers that are attempting to apply direct response rates to every bit of communication. It doesn't work that way.

People who only measure the immediate suck the results out of their long term.

If we were talking about fitness, I might liken direct response marketers to people who step on the scale every morning to check their weight. If the scale reads minus one pound, they feel successful. If the scale reads plus one pound, they feel defeated.

Ask someone trying to lose weight and they might even confess that anytime they gain a pound, they are compelled to inventory everything they did and ate the day before as if they could pinpoint its origin. Was it because they cut their cardio short for five minutes? Was it the turkey on their salad at lunch? Was it the half-glass of 2 percent milk they drank at dinner?

No wonder people who diet are so easily defeated. They are constantly measuring the wrong thing, thanks in part to this odd obsession with weight in most anti-obesity campaigns. But it's a mistake because body composition (not weight) is the cornerstone of a successful fitness program. And to successfully change your body composition, you need process goals as well as performance goals.

Marketing, advertising, and public relations work much in the same way. The total composition of your strategic communication plan has a greater long-term impact than any single piece or part. So while you can measure the direct response of almost anything, one pound either way means nothing.

Where is direct response measurement starting to infringe on effective communication?

Public Relations. More and more firms are allowing themselves to measure the number of pickups, total impressions, and advertising rate value delivered by each news release. But doing so creates an erroneous impression that some releases or pitches are good and others bad. The truth is, however, that relationships with the media cannot be measured by whether or not a reporter picks up a story. Provided the pitches and releases are grounded in having news value, even if you think they are ignored, they could eventually prompt a reporter to call out of the blue looking for an expert source.

Advertising. Every now and again, I share the story of an attorney who was convinced that the bulk of his marketing budget should be invested in the phone book yellow pages. When asked why, he was perplexed that it wasn't obvious. They spend more money where they get the most response. But that wasn't true. The attorney only received his greatest response from the phone book because that is where he invested the most marketing dollars. A better composition, not more money, eventually delivered a better response.

Social Media. Social media specialists and search engine optimization experts alike are often quick to judge the quality of content — whether it's a video, blog post, or tweet — by any number of direct response measures such as likes, shares, or incoming keyword traffic. While these measures are always good to look at, they also skew the story toward the first impression and not the final outcome or total user experience. Marketers need to remember that reputation is built by the total body of work.

Journalism. More than ever before in the history of media, journalism has become a populist medium. Reporters are less likely to cover stories that the public may find interesting and much more likely to cover stories that the public already finds interesting, which is grounded in direct response. The recent death of one particular actor and comedian may even be the tipping point. I don't recall someone's death ever being exploited as much as this one. But the media won't let up because the response rate is encouraging the exploitation.

There are dozens of examples. It's why Mat Honan can produce a wacky reality simply by liking everything on Facebook. It's why the greedy coin algorithm will usually fail. It's why author-photographer Geoff Livingston couldn't reconcile how the algorithms see art. And it's precisely why most people quit exercising when they don't see their weight change (as muscle replaces fat).

So while direct response will always be worthwhile (especially when it is enhanced by creativity, timing, and proper targeting), it doesn't mean direct response measurements and other algorithms can be applied to everything. If they were then Vincent van Gogh would have been lost to history and the person you're mostly likely to marry is simply quantified by a successive run of good dates.

So don't be fooled. Good marketing only looks simple because it is complicated. Sure, direct response has its place (much like weight) but only if your process goals and performance goals are designed to deliver the right strategic communication composition. And that's the truth, "like" it or not.